my work

essay + written task

home

“To restrict the artist is a crime. It is to murder germinating life”

In this written study, I will be investigating the work of Egon Schiele, and his captivation with all things revealing. A protégé of Austrian painter Gustav Klimt, the founder of the Viennese Secession, Schiele is renowned for his psychologically and erotically charged portraits, that depict himself and those close to him. In his teenage years, Schiele idolised Klimt and the two developed a close friendship in 1907 with Klimt becoming Schiele’s mentor, leading Schiele to acquire similar artistic methods and traits. The Viennese Secession played a significant role in the broader Art Nouveau movement, and with Klimt’s Art Nouveau-inspired style, it was no surprise that Schiele picked up on this in his early works, particularly in the way he represented the female form. However, it was clear to see Schiele’s own style appearing, even in these early works, and in some ways, he was able to directly contrast Klimt’s radiant, rich, golden palettes and patterned surfaces, in the way he opted for muted colours, fashioning an outcome that feels almost dehydrated, which is allusive of decay rather than growth. This is something that can be seen throughout Schiele’s work, especially in his landscapes, which seem to be somewhat ‘unsung’ in comparison to his portrait work. Born and brought up in Austria, Schiele went on to live his short 28 years of life there. With his father dying when Schiele was only 15, it is said that this event struck him, and can be used to explain why he sought solace in the dreary side of decay, death and sexuality – “I don’t know whether there is anyone else at all who remembers my noble father with such sadness”. In 1909, Schiele was invited by Klimt to exhibit some of his work at the Vienna Kuntschau, and coming away from this exhibition, he began exploring the human form and sexuality. From 1910-12, Schiele took part in exhibitions from Prague to Budapest, Cologne to Munich and then to Paris. In 1911, Schiele met Walburga Neuzil, who became his muse and lover until 1915. The pair left Vienna for Krumau, a rural town that is now a part of the Czech Republic, and the birthplace of Schiele’s mother. Eventually the two left Krumau, after complaints were made by locals about the teenage girls hired as nude models for Schiele. In 1912, he was arrested for seducing an underage girl, spending 24 days in prison. Schiele created a series of 12 drawings depicting the discomfort he felt in his jail cell. The relationship between Neuzil and Schiele ended abruptly when Schiele proposed to Edith Harms, who was introduced to the artist by Neuzil herself. Returning to Vienna in 1917, Schiele co-founded the Vienna Kunsthalle with Klimt and participated in Vienna Secession’s 49th exhibit in 1918. That same year, Vienna was hit by the Spanish flu pandemic. Schiele died from the flu three days after his wife, Edith, who was six months pregnant. With the creation of more than 3,000 works, Schiele became a crucial figure in the Expressionist movement. Expressionism originated in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century, with the sole purpose of the movement being to express the meaning of emotional experience, as opposed to physical reality.

With a population of 2116 (as of 2020), Stein an der Donau is a district of Krems au der Donau, in Lower Austria. Lying on a relatively narrow stretch of shore at the beginning of Wachau, the settlement area of this village is constricted in an east-west direction. Taking regular visits to the Wachau Valley and painting multiple versions of Stein on the Danube, Schiele associated this location with a deep longing for his childhood. Many of Schiele’s landscapes depict tiny medieval towns, with the majority of them being in Lower Austria, and they all demonstrate the solid connection he had to his hometown of Tulln. Out of the multiple versions Schiele completed of the same landscape, this description of Stein au der Donau (or Stein on the Danube) seems to be the ‘cheeriest’, like a warm, optimistic, summers day. The shade of bright green layered throughout, with the deep browns and bright reds create a different atmosphere to most of Schiele’s landscapes – it feels bright and hopeful, in comparison to the melancholy sentiment projected from many of his landscape paintings. There is heavy emphasis on the cliffs in the bright shades of cream and beige, which are contrasted by the grass green that is sandwiched between each layer of white; together, these colours hold a sense of joy and vibrance. Contrasting all of this, however, is the river at the bottom. Murky and gritty, filled with tinges of brown, this part of the painting reflects the majority of Schiele’s work, and brings a sense of reality to what could be seen as a radiant, vivid landscape. Immediately, I find my eyes drawn to the uppermost section of the image, with the bright cliffs and decorative, storybook buildings. Comparing these elements to the river, its still clear to see Schiele’s more gloomy aspects glimpsing through in the form of the river. The way Schiele has portrayed the buildings here in pretty even, solid rows again directly contrast from a lot of his rickety, precarious depictions of built environments.

A recent essay -

"A study of Egon Schiele's landscapes"

Stein on the Danube, 1913

(seen from the south)

Stein on the Danube II, 1913

In direct comparison to Stein on the Danube, I will also be looking at Stein on the Danube II. Another one of several paintings that described the rural town of Stein au der Donau, Stein on the Danube II has a completely different tone to it, compared to the previous. The lack of colour is apparent, with beige being the overriding shade. Dashes of light blue and green highlight the river and hills, seeming to be the only alive, moving subjects present. Here, Schiele is looking down on the town, the opposite to the image previously. This angle ensures that the river takes up half of the canvas, which contrasts to the small glimpse of river shown in in Stein on the Danube. The once bright white and green cliffs are absent, and the buildings are the ultimate focus here. Unlike the previous painting where the buildings were layered in tidy rows, here in Stein on the Danube II, there is no real ‘block’ of houses as they’re scattered in sections.

I find it fascinating how Schiele has produced paintings of the same location, with both of them having entirely different atmospheres. It feels as if he visited Stein au der Donau at two different points in his life, with one being a time of prosperity and the other, a time of despair. It’s easy to imagine Schiele sat up on the cliff, painting Stein on the Danube II on a gloomy day, at a miserable time in his life, and him sat on the bank, opposite the tiny town with the river flowing by, painting Stein on the Danube.

City in Twilight (Dämmernde Stadt) 1913 -

Depicting the birthplace of Schiele’s mother, City in Twilight is a fictional, almost dream-like view of Krumau - as opposed to a literal landscape, City in Twilight is an emotional landscape. I find myself captivated by this painting of Schiele’s, maybe more than any other – there is something about the complexity of the multitude of structures at the top, combined with the drastic blank, open space at the bottom that is almost enchanting. A common theme in Schiele’s landscapes is the lack of life present. However, there are always hints that life does exist, in the occasional washing line, or in this case, brightly coloured windows that suggest that the buildings are occupied. City in Twilight has a notable history; painted in 1913 by Schiele, the first sale of the piece was settled by Klimt to a young architect by the name of Hubert Young. After Young was killed in the last year of the first World War, the painting was passed onto another collector, before being sold in 1928 to a woman called Elsa Koditschek, a 43-year-old Jewish widow in Vienna. A letter dating back to 1946 was written by Koditschek and addressed to her son and daughter, illustrating what had happened to her during the Second World War. Koditschek wrote about how, in August 1940, she had received a requisition that stated that she had to give up her apartment within 14 days to a Nazi SS officer, who was to move in with his family. Upon hearing this, Elsa Koditschek put the Schiele painting, a bed and two chairs in the apartment above, belonging to her neighbour. After being given the notice that she was going to be deported, in 1941 Koditschek went into hiding, spending several years inside a friend’s house. Koditschek’s neighbour visited her, informing her that she’d sold the Schiele painting that was left with her. After it became known that Koditschek was in hiding, she managed to make it back to her own apartment building, living with her upstairs neighbour, watching the Nazi officer from above and surviving the Holocaust by staying hidden. Since it’s been out of the public eye for over 50 years, City in Twilight is in pristine condition to this day. Schiele’s pencil marks are still visible, and the colours showing the lit-up windows remain just as bright, almost as if it has just left the easel. The amount of history behind this painting gives it so much depth - not only is it a masterpiece by Schiele, but it is also a part of an incredible story of survival. The precarious, unproportionate nature of each individual house plays a role in the overall ‘rickety’ feeling of this painting. Sharp, triangular angles and shapes are juxtaposed by the mottled, velvety textures. Vivid white, used to portray lit up windows, contrasts with and stands out against the earthy tones in the buildings that encase the windows. The prickly, almost three-dimensional rooftops give the idea that, if you were able to place your hand on top of the painting, it would feel sharp and jagged. Something that Schiele does in the majority of his landscapes/townscapes is use a darker tinge of colour along the edge of every shape created, giving an intense depth to each section of the painting - seen in City in Twilight, in the way that every line on every structure is hollowed out. Schiele held the small town of Krumau close to his heart – the feelings of his youth paired with the enchanted landscapes provided infinite amounts of inspiration for the artist. In City in Twilight, the detail and attention Schiele included proves how special Krumau was to him.

Four trees, 1917 -

Known for being Schiele’s most famous landscape painting, Four Trees was created a year before his death. Similar in subject and colour to Setting Sun, 1913, Four Trees feels warm and mellow, in stark contrast to Stein on the Danube II, and even City in Twilight. Schiele wrote in a letter to the collector Franz Hauer in 1913: “I mainly observe the physical movement of mountains, water, trees, and flowers now. Everywhere one is reminded of similar motions inside the human body, similar stirrings of pleasure and pain in plants. Painting alone is not enough for me; I know that one can use colours to establish qualities. When one sees an autumnal tree in summer, it is an intense experience that involves one’s whole heart and being; and I should like to paint that melancholy.” The most notable point upon first viewing this painting is the varying condition of the trees, with the trees on the outside being the healthiest and fullest. This could be said to symbolise the idea that being on the outside of society, as opposed to a more mainstream lifestyle, leads to a happier and healthier life, full of freedom. However, the tree with no leaves could also be interpreted as being the outsider, in the obvious way that is it profoundly different to the rest. Three days after getting married to Edith Harms in 1915, Schiele was ordered to report for active service in the First World War. Stationed in Prague, Schiele’s commander gave him a disused storeroom to use as a studio. By 1917, he was back in Vienna and ready to focus on his artistic career. With this in mind, Four Trees feels even more comforting, – Schiele was married, back home and with his life as back on track as it could be. With the sun acting as the centre point between the four evenly spread trees in the foreground, the contrast between light and dark provides an atmospheric vista. The warm, silky clouds lay horizontally at the top, juxtaposing the bumpy, rolling hills on the lower half. The darkness of the hills ground the detailed sky, holding the whole thing together. Compared to Stein on the Danube II, Four Trees feels optimistic, which is something not seen from Schiele very often. Despite this, the element of death is still present, in the way that the leaves on all four trees have turned red, and one is almost bare. This is suggestive of the end of the natural cycle that always concludes in death. It’s been said that Ferdinand Holder’s Autumn Evening 1892, provided inspiration for Schiele’s Four Trees. Comparing the two, the most significant similarity is the subject of chestnut trees against a sunset. Other than that, the atmosphere in each painting is dissimilar and evokes an entirely different mood, in the way that, unlike Four Trees which is somewhat horizontal in composition, Holder’s Autumn Evening follows a strict point of perspective with trees following a path into the distance.

Egon Schiele will be remembered for years to come, not only for his gritty yet fascinating figurative work, but also for his remarkable landscapes. He worked in a way that will never be accurately replicated to the same degree – his use of texture in his landscapes alone sets him apart from any other historic artist, not to mention his use of shape, line and colour. From being influenced by German Art Nouveau, to influencing the Vienna Secession movement and Expressionism, Schiele lived a life full of turbulence and it shows in his work. The way he was able to effortlessly capture the essence of desolation within his landscapes is something that he should most definitely be remembered by - every single landscape study feels like a snippet of history. I think the idea that there were never any people seen within his depictions of these environments is interesting in the way that he went from one extreme to another, from in-depth figurative work to fully landscape work; no in between.

http://www.egonschiele.net/four-trees/

https://www.theartstory.org/artist/schiele-egon/

Egon Schiele: Landscapes, Rudolf Leopold

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-liverpool/exhibition/life-motion-egon-schiele-francesca-woodman/five-things-know-egon

http://www.progetto.cz/magia-e-amore-il-rapporto-fra-schiele-e-cesky-krumlov/?lang=en

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egon_Schiele

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5rhlv6JI7g0

https://www.austria.info/en/culture/artists-and-masterpieces/egon-schiele-and-his-melancholic-landscapes

https://second.wiki/wiki/stein_an_der_donau

Written portfolio task

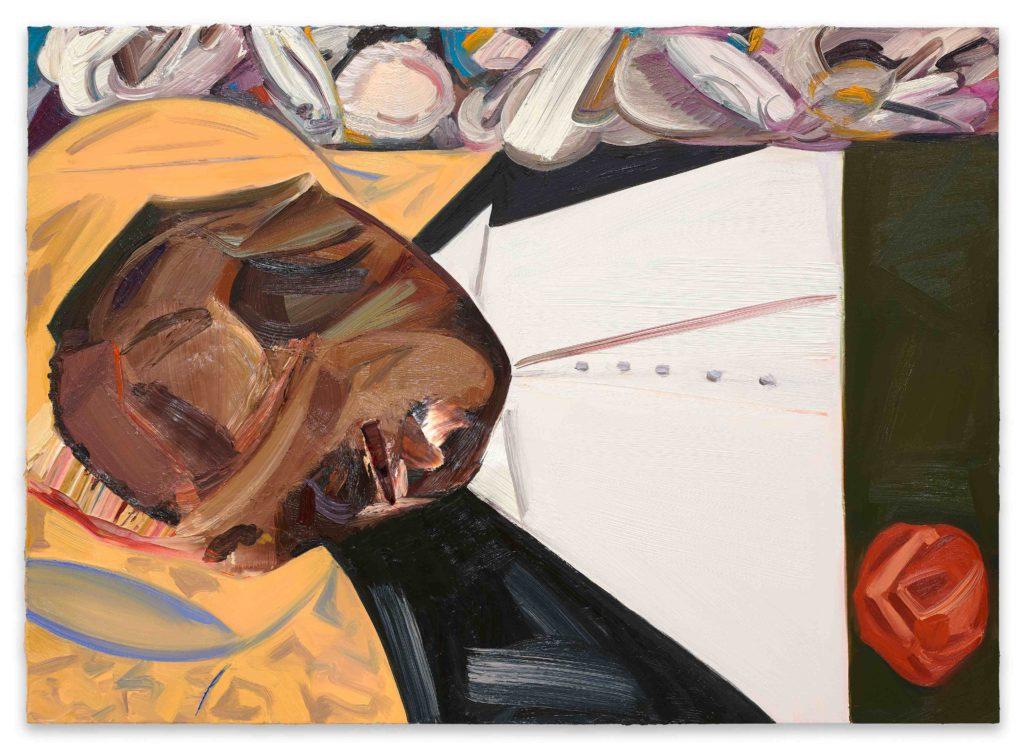

Depicting the mutilated body of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African-American boy from Chicago who was brutally murdered in 1955 by two white men, for allegedly flirting with a white woman, Dana Schutz’s ‘Open Casket’ caused controversy when it was presented at the Whitney Biennial in 2017. Schutz, a white artist, created the painting in 2016 as a response to media coverage of police brutality, in particular, black men being shot by police. Even a quick look through Schutz’s work shows that she is an artist of spectacle, someone who captures figures and scenes in a dysfunctional but incredibly admirable way, and the majority of her work could be seen as offensive to the human eye simply due to the sheer morbidity of it. Soon after ‘Open Casket’ was unveiled at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, protest began, with writer and artist Hannah Black issuing an open letter to the museum’s curators stating, “the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about black people”, “the painting must go.” The idea of contemporary art being built on white privilege and white supremacy is very much relevant in modern civilisation, and that is no different here, with Black adding, “white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others”. Conversations should be welcomed, everybody can learn from everybody, whether that’s learning what not to do, or how to go about things differently than the last person. Could destroying Schutz’s ‘Open Casket’ in turn confiscate the history behind Emmett Till, and the vicious end that he faced? A Quote from German Poet Heinrich Heine, “where they burn books, they will, in the end, burn human beings too”, ties into the notion that destroying the painting, which holds history and a (questionable(?)) sense of cultural value, would only lead to further hurt, or, inevitably wouldn’t change the past. The extremely uncomfortable nature of the painting is entirely unmissable, with light and dark shades conveying a sense of ruthless disfigurement within Till’s face, however it could still be seen as naïve in its gesture. Artist Lisa Whittington, a black woman who has also painted portraits of Emmett Till, told NBC News, “while I appreciate Schutz’s courage, and attempt to understand, for me, her understanding is not deep enough and careless. The horror was too gentle in her work,” “she did not tell a complete story,” “she downplayed the details and the emotions his death represented.” The pain and suffering felt by Emmett Till, by his mother and family, by people of African-American descent, or by anybody who related to his story, is downplayed and lost within Schutz’s painterly style, lost within Schutz’s aesthetic. Maybe the empathy that Schutz’s undoubtedly had, comes across in her work as her being conceited instead of empathetic. The controversy ‘Open Casket’ caused has absolutely led to conversations that need to be had, and it remains important for artists to be able to represent, in order for these conversations to be started. As stated by Schutz herself, “it is better to try to engage something extremely uncomfortable, maybe impossible, and fail, than to not respond at all.”

Open Casket - Dana Schutz, 2016